By Dylan Morris; The Whetstone Â

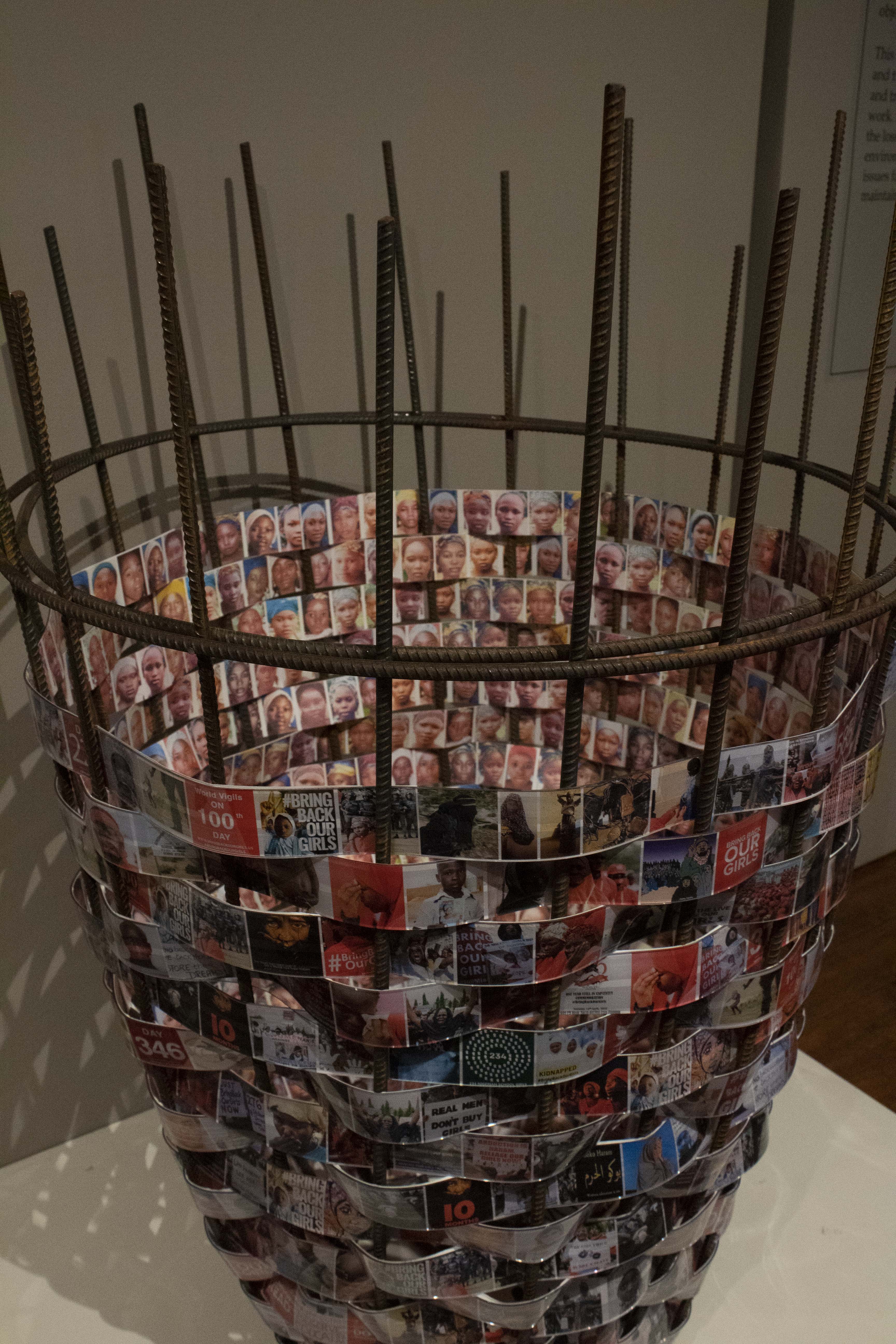

A new national art exhibit made its way to Dover in the form of baskets.

The Rooted, Revived and Reinvented: Basketry in America exhibit continues it’s tour of the nation by stopping at the Biggs Museum of Art through April 28.

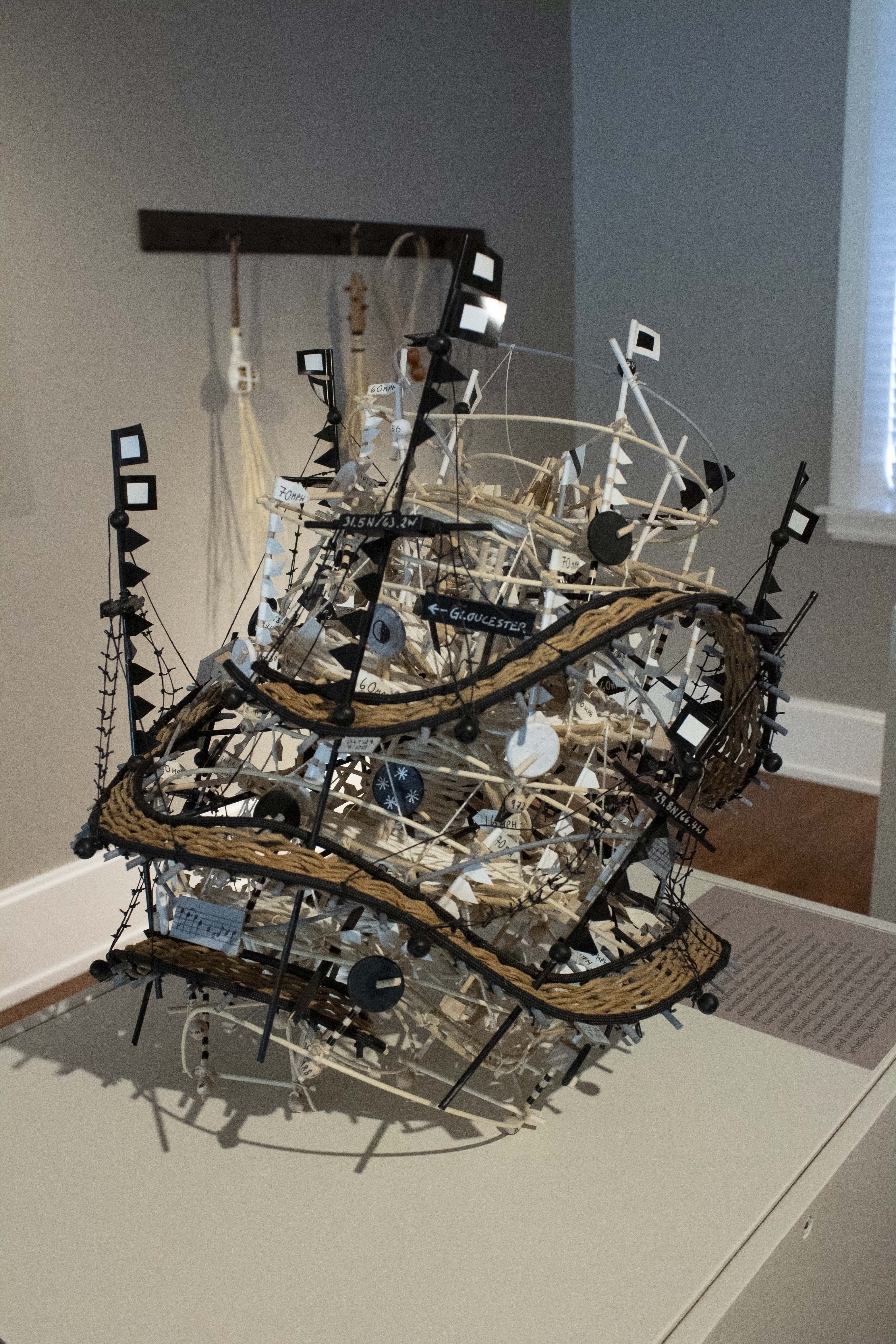

The exhibit chronicles the history of American basketry, including some of the more modern interpretations of basketry as an art form.

“It talks about a lot of the cultural influences of basket making, the Native American, African American and Western European influences in the 18th, 19th and early 20th century,†curator Ryan Grover said. “It also shows how artists have used basketry techniques to create sculptures and fine art objects.â€

He said the baskets may be seen as aesthetic objects that interpret the artist’s personal point of view.

The exhibit is separated into “Cultural Origins, New Basketry, Living Traditions, Basket as Vessel, and Beyond the Basket”. The exhibit was originally assembled by University of Missouri Profs. Jo Stealey and Kristin Schwain.

It is a comprehensive exhibit of nearly 100 art pieces from artists throughout the country.

“We look for things that we think would be popular to our part of the country,†Executive Director Charles Guerin said. “We thought it would be thrilling to have the exhibit, so we decided to bring it here to Dover.â€

The exhibit is scheduled to tour the country through next year.

All exhibits at the Biggs are open from 9-4:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday, and 1:30-4:30 p.m. on Sunday.

Admission is $10 for adults, $8 for seniors. Students, active military personnel and children under 18 are admitted for free.